One Saturday morning in 1988 two British Army corporals, David Howes and Derek Wood, accidentally drove their car into an IRA funeral procession.

They were surrounded, pulled from their vehicle then stripped and taken to waste ground where they were shot.

The incident, which became known as the ‘Corporal Killings’ was filmed by television crews who happened to be covering the funeral, and the horror was beamed directly into living rooms around the world.

The image of Father Alec Reid administering last rites to the bloodied and battered corpses is seared in the memory of anyone who saw it.

After years of peace, following the Northern Ireland Peace Accords, it’s difficult to recall just how violent and turbulent a place Northern Ireland was during ‘The Troubles’.

It is certainly easier to try and forget it.

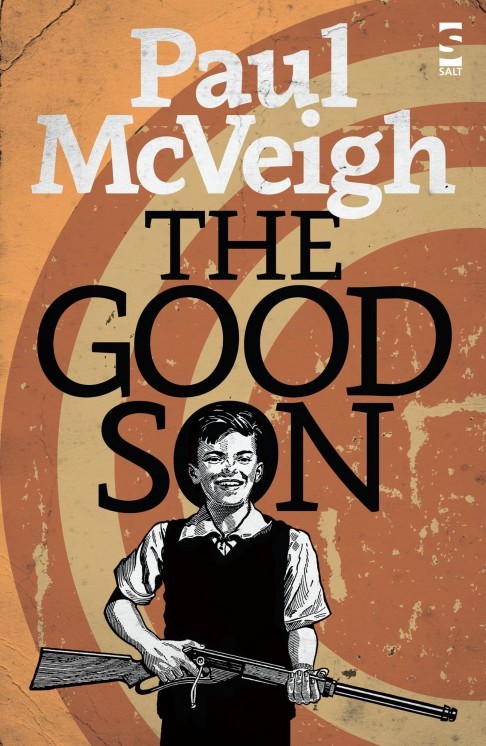

But the full horror of that Saturday in 1988 came back to me as I read Paul McVeigh’s ‘The Good Son’.

In the book, Mickey Donnelly, the main character, is accidentally caught up in a similar incident. The minibus in which he is travelling is stopped at a Protestant checkpoint and for one nerve-wracking moment it is uncertain what will happen. Will they be allowed to pass? Or does a violent fate await them?

As a kid, when I saw the news footage of the Corporal Killings I was gripped by panic and nausea. The full, visceral terror of that moment, the fear those men must have felt, was extreme. Even sat at a safe distance in a living room in Scotland, it was something I could feel.

I felt it again as I read that passage in ‘The Good Son’.

But you cannot avoid violence in a book which is set during ‘The Troubles’, and it is not something McVeigh evades. The bombs explode, soldiers are executed, loyalties are defended.

And against this backdrop of political violence, lives are lived. But they are lived under a threat of violence which is also personal – verbal abuse, threats, physical abuse, humiliation, machismo, the ‘background noise’ of sectarian hatred fuelling a day-to-day violence which is so familiar it is barely registered.

But Mickey Donnelly notices it and he recoils from it.

His presence in the story, naïve, funny and sweet-natured, leaves you wondering what it must be like to grow up in such a place.

How do you survive a thing like that? What impact does it have on your psyche?

Mickey Donnelly has a few survival strategies – perhaps the only strategies which are ever really available to us under such circumstances.

He has hope, he has love, and he has imagination.

Hope

It’s become something of a cliché, perhaps a little sentimental even, to believe that hope is a thing that can carry you far. Holding on to dreams, believing in them, is for the naïve, is for the kids. Kids like Mickey Donnelly.

Certainly when you take a look at the bleak reality which surrounds him, you can’t help but wonder if his hope is unfounded.

But if this is the case then where does that leave him? Without hope, what will become of him?

The shadow of Mickey’s father is a looming presence in this regard. Here is a man who has kept his distance from the IRA only to discover that passive resistance offers nothing beyond alcoholism, poverty and humiliation.

Mickey certainly despises him, and sees in him a weakness which has beleaguered his family and caused his mother nothing but heartbreak and suffering.

But he is a man who more than understands what a lack of hope brings, a man who embodies it even. He clearly regrets his choices and tries to help his young son understand that dreams of escape are vital.

“Look at this place” he says starin’ down at Ardoyne. “Is there anywhere more depressin’? When you grow up son, you get out of here, won’t you? Biggest mistake of my life stayin’ here.”

Mickey is too young to fully comprehend the pain of hindsight and regret, of course. But he catches glimpses of it at times. Up in the hills surrounding Belfast, atop ‘Napoleon’s Nose’ he gets a sense of what his father is talking about.

‘I look out to the Lough and there’s a ginormous ship headin’ out to sea. Out of here. Goin’ anywhere you want. Like Da said. He was tellin’ the truth about here. About the view. About the ships. But I still hate him.’

But at such a young age, the consequences of his father’s lack of hope are all that Mickey can see. The mess of the father’s life threatening to cascade on down the line and topple the son. No kid can fully comprehend the journey that a man takes to get from hope to despair.

So he hates his father even as he is teaching him something, even as he is pointing out the escape route. All Mickey knows is that his actual escape route, a prized place at grammar school has been cruelly taken away as a result of his father’s actions. Snatched away because there is no money to send Mickey there.

And when the father asks:

“Have I been a good daddy? Tell me, have I, son?”

It’s easy to react and say “No, no you haven’t.”

But our parents always give us something, even if it’s only to show us the path we shouldn’t take. And Mickey Donnelly is a smart kid. He knows enough, even if he’s not aware of it.

He sees enough of the glue sniffers and the IRA lackeys to see the damage defeat or simple acceptance of the status quo can bring.

He understands that it is far better to stand on top of a hill and jump for joy at the possibilities; to see beyond to something better, something new, than it is to stare downwards and despair.

From the perspective of 2015, after so many years of peace in Northern Ireland, it’s a powerful reminder that hope, for all its apparent naivety and impossibility, can be the driving force behind real change.

Following the death of Father Alec Reid, the priest who had administered last rites to those British soldiers, details emerged of his quiet and persistent efforts to bring about lasting peace in Northern Ireland. On the day of that brutal murder, he was carrying a letter from Gerry Adams to John Hume, the latest missive in a long drawn out personal effort to bring the two sides together.

A task many thought impossible. Hopeless even.

And but for men such as Father Reid, and the hope they cherish, who’s to say it isn’t so?

Love

Mickey Donnelly is at that awkward age, on the cusp of puberty, but a child still and when he loves, he is effusive about it, demonstrative.

He plays with his younger sister Wee Maggie, holds her hand, dresses her up and gives her “our special look, the one we’re not allowed to give anyone else”.

He is kind to his mother, looks after her and tries his best to make her smile “her Ma smile. The one you try hard for.”

But demonstrative love, affectionate love in a boy this age is not always appreciated and for Mickey, his affectionate nature makes him an object of mockery. His gentleness and naivety scorned as “gay”.

Like every child Mickey has to learn that overt signs of love or affection are not always welcome and that other ways of loving and understanding others need to be learned.

In one poignant moment, as he watches his mother cleans the back yard, he begins to understand that he is seeing something more than just a woman scrubbing.

‘Ma puts her hands on top of the brush pole and rests her head down on them. A wee break. She must be wrecked. She looks up, leans the brush on her chest and twists her weddin’ ring on her finger, starin’ into space. Ma’s spacin’ out like me. Mammy thinks too. I never realised. I wonder what goes on in there. I don’t try to telepath her cuz her brain would be like Fort Knox.’

There is always a moment in childhood when you begin to understand your parents in a new way, a way that is different from the way you loved and understood them as a very small child. A moment when you begin to understand them as people in their own right – people who think and feel the same as you do.It’s the empathy we all need to survive and thrive. The empathy which makes us “good” sons, daughters, wives, mothers, husbands, fathers.

It’s the empathy which, in the end, ensures our social fabric isn’t torn apart by those forces in our nature which are not “good”.

But it’s also a part of our psychological make-up which can be damaged by exposure to violence.

It’s too facile an analysis to state outright that the community in Ardoyne is so inured to violence that exposure to displays of affection as innocent and open as Mickey Donnelly’s leave them unable to respond with anything more than sneers or laughter -but Mickey’s refusal to stop expressing his affection, may just be the very thing which saves him.

Certainly the whole concept of love is something which is called into question in The Good Son.

Mickey, in the end, is guided by love when he takes the decision to act to save his family. He is driven to act because he loves his mother and wants to protect her, and in that regard, although his ultimate act of betrayal can be seen as something morally dubious, it is driven by something good and has consequences which are good – which leaves the reader with a question.

[tweetthis]If good outcomes comes from ‘bad’ actions, can we accept them?[/tweetthis]

In Mickey’s case I think we probably can, but what about those members of the IRA, such as Mickey’s brother Paddy, who believed they were driven by a similar force – the love of Ireland? The actions they took, however morally reprehensible, were, in their judgement, ‘good’ because the cause itself, driven by this ‘love’ justified the violence. Love, it seems, can lead us into a moral quagmire.

Mickey Donnelly is slowly learning this and the final denouement, shows he is clever enough, emotionally developed enough, to navigate the grey areas of morality and come up with a solution which ultimately serves the greater good.

He makes things better, brings about a happy ending, because he loves his ‘Ma’.

Sometimes it really can be as simple and beautiful as that.

Imagination

All kids distract themselves, it’s part of what play is all about. Certainly, all of the kids in The Good Son are full of imagination and laughter. They put on plays in their garages, write stories in school, craft helicopters from lollipop sticks, sing their hearts out.

But Mickey Donnelly imagines more than most. He imagines superpowers – invisibility, telepathy. He talks to his dog. He has secret conversations with his sister.

His is a very rich internal life and a wonderful contrast to the realities around him. It allows him to see beauty where others may see only chaos. He sees ruby red treasures in the wasteland, puts the broken glass to his eye and, literally, sees the world in a different light.

But his imagination also provides an escape when the going gets rough or the world gets too much.

Mickey Donnelly, The Incredible Invisible Boy. Son of the Invisible Woman. I will do works of great good around the world. I will destroy the forces of the Evil Fathers and Big Brothers. And when I get sent out of the room cuz they’re talkin’ big people’s talk, I’ll slip back in and get all their dirty secrets and blackmail everybody to get money to get four plane tickets to America, for me, Ma, Wee Maggie and Killer.

As a child, this type of magical thinking isn’t something he questions too much. Sure, he understands it is nothing more than that, he knows the world will not be changed by it, but there is an underlying sense that he knows it is important to keep looking at the world this way, to keep believing in something, to keep imagining something, because perhaps, just perhaps, it can be willed into existence – this better life, for him, for his Mammy, for his sister.

When is it we lose this ability to believe in dreams, I wonder?

As adults, we are careful to look at the world ‘responsibly’, ‘realistically’, and we imagine this approach to be a good thing. It’s practical. It helps us ‘get things done’. But spending time with Mickey Donnelly, I started to wonder what it is we lose when we stop imagining and dreaming this way.

Because it’s more than just our fantasy worlds that vanish into adulthood.

Imagination provides us with an escape route – a way of stepping out of our lives to envisage things in a new way, in a different way. It offers a new perspective, and, in some respects may even be the source of those other survival strategies – hope and love.

When we step outside ourselves we learn to see things in a different way – even those things we may fail to understand or even hate. Even those people we have learned to hate as “other”.

And I think it is this, above all else, that Mickey Donnelly understands, even without knowing it.

That good things come from hope and love and imagination.

That it’s the good sons, the dreamers, who, one way or another make the world a better place.

You can also read (and listen to) my interview with Paul McVeigh over at Litro Magazine

Many thanks to Jen Hamilton-Emery at Salt Publishing for the review copy.